Emily Barker (they/them) is an LA-based artist, model, and disability justice advocate, though many—including myself—got to know Barker via their Instagram account, @celestial_investments. Barker manipulates popular social media aesthetics, like seductive mirror selfies, to catch the eyes of their nearly 40,000 followers, leading them to paragraphs-long captions describing the systemic injustice experienced in daily life as a disabled person in the United States. It was through Barker’s Instagram that I learned the extent to which the US welfare system maintains an intersection of poverty and disability, as well as the sheer extent of the astronomical expenses such impoverished and disabled people are then expected to cover. Outside of the virtual realm, Barker’s conceptual, sculptural, and installation works function equally for two disparate audiences: to enlighten the able-bodied about daily life as a disabled person, and to uplift disabled people by emphasizing that accessibility can go hand-in-hand with both dignity and beauty. We spoke via Zoom in March 2021. —Eliza Levinson

Eliza Levinson How would you describe your practice?

Emily Barker I am a conceptual artist, an installation artist, a disability advocate, and I write and build stuff. I feel like a jack of all trades, really. I am what I need to be. But what I want to be doing is making art.

EL Would you consider social media to be part of your artistry? What role does Instagram play in your practice?

EB Instagram wasn’t a part of my practice before, like, two years ago. Before that, I was making conceptual art, giving readings, and doing advocacy. Now, I have around 40,000 followers, and I’m basically just using it to lure people into learning about ableism. It’s a double-edged sword, because I could have 100,000 followers if I just posted selfies wearing not a lot of clothes and doing identity politics stuff.

But as my grandma would say, “Are you gonna cut your nose off to spite your face?” What’s the point of having a vapid social media presence where no one learns anything and they think all people with disabilities are now fine because you’re fine? Or where you’re presenting an inaccurate portrayal of disability in order to get followers? For me, what’s important is, at the end of the day, more people learn about capitalism, and how that relates to people who are marginalized, and how that relates to, and reinforces, ableism.

EL It definitely worked for at least one person—your Instagram has taught me so much about what disabled people in the US have to go through.

EB People message me that maybe once or twice a day. That’s the reason I keep doing what I’m doing, because I’m not being paid for it. It’s a shit ton of work. I’m very grateful for the people that come to my page willing to learn, because most people still don’t know what ableism is, and most people don’t recognize that disabled people don’t have equal rights.

I was a traditional painter, and then my accident happened. I couldn’t make art about the stuff I was making art about before, because my whole body and my life and my experiences were different, and what I was thinking about was different. And then I was making pieces like Single Use Only (2017), which is 120 catheters mounted on the wall, because that’s my life now. I’ve now been disabled for a decade. What else do I make art about, except for this?

I can’t come to art from the perspective of an able-bodied person who doesn’t have to think about these things every waking moment. I want to get back to that place: I want disabled people to have the freedom to do whatever they want, and not feel so bogged down and burdened by the world that they find it necessary to change it because no one else is.

It’s from a place of love for other disabled people, but also from this recognition that the other disability advocates on social media were not talking about the intersection of capitalism and ableism. Or they weren’t talking about the intersection of poverty and disability. And they weren’t talking about austerity and eugenics.

I really believe that people are born inherently willing and curious to learn and be open to these things if we’re taught to be caring, loving, kind, and considerate. And we’re not. It requires all of this undoing of our own socialization. A lot of people just want to do visibility, identity politics, toxic positivity, because that’s what the algorithm wants, at the end of the day. And what we’re doing is basically reinforcing the issues that exist with social media, instead of interrogating and pulling them up out of the ground.

EL Using Instagram in the way that you do is something of a double-edged sword, because theoretically, social media gives everyone a voice, but these platforms aren’t fully democratic, because they’re ultimately run by capitalist companies.

EB I’m making money for a company that sucks, and that punishes me for posting things that are too political. I’ve almost had my account taken down multiple times, so I’ve had to water my content down a lot. But at the same time, I’ve been stuck in my house, not because I couldn’t drive, but I didn’t have enough money to have a car or to have the hand controls that cost $2,500, or to have the modifications that cost literally installing them $3,000, plus the lift. For years, I didn’t have caregiving. Instagram was the only platform where I could actually articulate any of my thoughts.

So, I’m trying to use this painful algorithm to just get people to understand these ideas, but at the heart of everything, I’m an artist, and I want to make art. And so everything I do is just to get to a place where I can make art. But when you don’t have an accessible place to live, and you can’t use your kitchen or turn around in your bathroom and you could barely get up your driveway as of a year ago because you didn’t have this $5,000 wheel to push you up your driveway…art is not a lucrative thing, but when you’re disabled, it’s an extra layer of: you can’t even find a cheap apartment that’s falling apart to live in. There’s so many barriers to me making art. But our culture is a society of the spectacle. And so I’m just playing into that.

I don’t think art changes the world at all; I think direct action and policy change the world. I think art is a really good medium to emotionally affect other people in a way to get them to understand something that they wouldn’t have otherwise.

EL On your Instagram, you talk a lot about the intersection between poverty and disability. Can you talk a bit about that?

EB This makes me so emotional. It makes me so upset thinking about it.

I was 19 when my disability happened. I wanted to go back to school, and my parents didn’t know how to navigate SSI, and they couldn’t really do much for me. I had a really nice woman at the physical rehabilitation center who was really great about getting me set up for SSI.

I learned that if you become disabled before you’re able to pay into social security in the United States, you are unable to ever get actual disability. Like, ever. Unless I got off SSI and was able to work a full-time job for five years. So, all of these kids who were born disabled, who [have] never, and can’t work, will never be able to get more than $730 to live off of, and are not allowed to have more than $2,000 including that $730 of SSI, in their bank account during a month. It’s not a total of $2,000 extra: you only get another $1,200 that you’re allowed to have in your bank account.

My assistive device cost $5,000. My wheelchair cost $26,000. The real CRPS treatment is $30,000 out of pocket. I’m part of the 1% that is the most expensive for health insurance companies: my medical bills are, like, $1,500,000. Within the first six months [after my accident], I had already hit, like, $1,000,000 of surgeries. It was not because those surgeries cost that much. I could probably go to Germany and get it for, like, $1,000.

People have lost their SSI due to GoFundMes that they’ve raised. You can’t be disabled and live off of $2,000 a month. It’s just impossible, given the ridiculous healthcare costs of medical devices and assistive devices and mobility devices. I’ve been penalized for raising money to even get parts of my wheelchair fixed, or buying a used wheelchair from a friend: they’ve taken money out of my SSI for a [period of time], so my payment went down to, like, $600. You can’t live off of that. Like, anywhere. You can’t live in a rural place, either, because then you can’t get to doctor’s appointments. And if you have a very rare disease, you can’t live in the middle of nowhere. You have to live in a major metropolitan city, because there aren’t neurologists for your rare-ass disease elsewhere. If you have children, you lose your eligibility for SSI, and if you get married, you lose your eligibility for SSI, because your partner should be able to financially take care of your incredibly expensive needs. We’re not able to live normal lives.

People will say, “Oh, my aunt or my uncle with back problems is on disability, and they get $2,000 a month,” and it’s, like, yes, because your aunt and uncle got disabled later in life, after they had worked, and the amount that you get is associated with how much income you earned. Your aid is a direct result of how much you were able to be capitalized off of while you were able-bodied.

The problem is, when you have a group of people that are not able to mobilize in the way that able-bodied people are, to do [things like] direct action, which usually involves inconveniencing the system enough [to make change happen], how do you get radical change?

Disability is the one thing where you can wake up and be the next day. Disability is the one thing that you can always become, no matter who you are. For disabled people, the image of us brings up so much internalized ableism. Right now, I see able-bodied people getting applauded for regurgitating disability talking points, but if it’s disabled people talking about it, it’s not okay, because it’s too depressing. You have to have a proximity to looking able-bodied or being successful for people to want to listen. When you’re impoverished and you’re disabled, those are two things that, in a capitalist society, people don’t respect, because they think that you are worthless.

EL You once said that “people do not realize being ‘able-bodied’ is a temporary privilege.” Can you talk about that?

EB Our bodies are really fragile. When your bodily autonomy is dictated by a horribly cruel system, then we are all going to suffer. My accident is a direct cause of the negligence of a landlord. If we didn’t have this system that incentivizes negligence, and incentivizes cruelty, and incentivizes toxic masculinity, and incentivizes the exploitation of everyone else, then we’re gonna have a lot of very sick people, and a lot of disabled people. And we do.

People look at the world, and they just think that everything—the way that everything is built, the way that all the systems exist—must be the best way, and that if you just follow the rules, you will be successful. When I had my ability to be a part of that [system] taken away from me, it made the reality very, very clear.

I don’t wake up in the morning sad. I have a beautiful life. I make everything the most sensual and enjoyable and delicious that I can, no matter what. I’m not a bitter, sad person. Despite the hardships that disabled people face, we are not suicidal. We don’t hate our lives. But people really need to start recognizing: wouldn’t it be better to live in a world where if you became disabled due to an accident or cancer or a rare disease, you could actually be able to live, take care of yourself, and be taken care of? I have hope, which is important. If you’re gonna see the reality of things, you need to make a little heaven for yourself.

EL Can you talk a bit about the materials you work with?

EB I just work with whatever material makes sense for that piece and that space. What would be the most beautiful material that is also functional? You’re working within physics, plus being disabled and poor. What material can you use, feasibly? So, that’s how my material choices come about, like everything else: out of necessity, and out of material I could find.

EL What are you working on now?

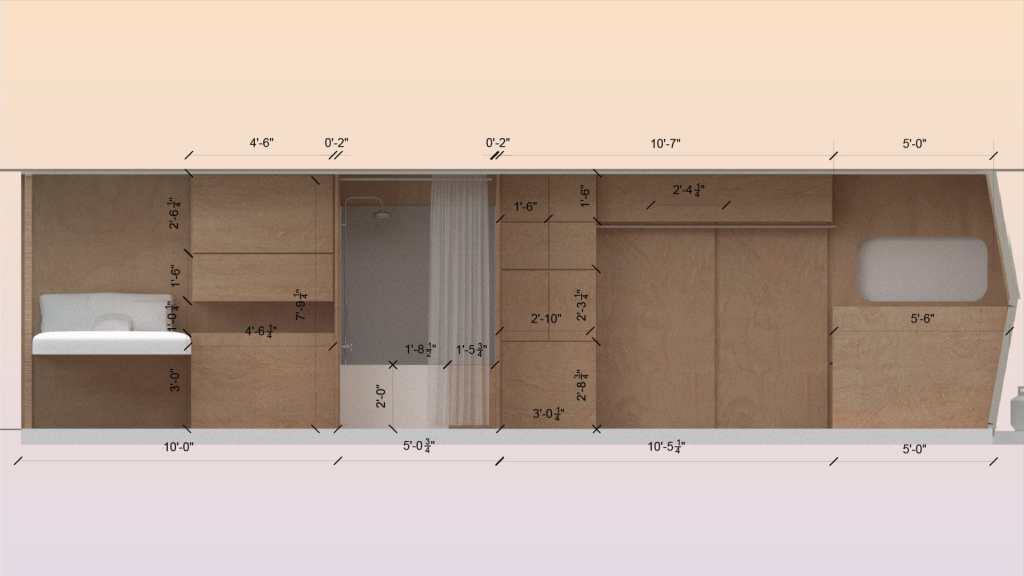

EB For a year, I’ve been building a completely wheelchair accessible domestic space; a dwelling. I want to show that accessibility doesn’t have to be this sterile or unattractive thing, because we have all these stigmas about accessibility being medical devices; ugly stuff. I mean, I love it, but I don’t want to live in it.

The RV that I’m renovating and gutting, Moving Parts, is all very warm. For example, it has a shou sugi ban—Japanese burnt wood—ceiling…It completely obliterates all of these preconceived notions of accessibility. It’ll be a space that able-bodied people would want to live in. Because one of the excuses that people always make is, “Oh, well, accessibility is too expensive, or it’s unattractive, or it’s unaesthetic.”

So, I’m building out this RV to deconstruct this idea that accessibility is far too economically inaccessible and it’s just too ugly. I want to show that not only can accessibility be affordable, but it can also be beautiful and unconventional. I think working within constraints breeds the most interesting outcomes.

How do we start conceptualizing and creating worlds that we all can live in, first and foremost, that is practical, but that we all would want to live in? This is the hardest thing I’ve ever worked on. But once I get one done, I want to make more for other people if they want one. ‘Cause how else will a disabled person be able to have a house to live in for, like, $40,000 that’s completely accessible? It’s as big as a New York apartment. Mine has three queen size beds.

EL Would you say you’re “staying with the trouble”?

EB I’m definitely trouble. And the powers that be give me trouble. I am a threat to Instagram, and all of these things that tell me that I don’t deserve to have the same things as everyone else. And I’m, like, “Actually, bitches: I do.”

I just want all disabled people to know that they deserve to have the same fucking things as everyone else, and the care that they want. Not the care that they need, the care that they want. Our lives should not be subjected to the whims, the kindness, of others. We should not be dependent on other peoples’ kindness to have the basic things that we need to survive.

Hey!

Did you love this article? Do you want more amazing content about all the incredible West Coast artists and art happenings? Your support makes it all possible.

Be an art lover ➵